Any man can be a father. It takes someone truly annoying to be a dad. At least, that’s what I tell the kids. It was a lesson I learned from my own father, and am still learning.

Mine was a happy childhood, spent mostly lazing about, playing games and avoiding anything that resembled hard work, especially at school. And my father was a loving man who, I realised, looked out for me.

When, aged 14, I brought home a school report that so brutally laid bare my shortcomings that it made my mother weep at the kitchen table, my father chose instead to focus on the PE teacher who had written that I was ‘a remarkable catcher of a ball’.

‘Well, it’s not all bad,’ he said, happily.

He was on my side. As he was when I was suspended for punching and breaking the nose of an annoying twot in school a year or so later. Called into school en famille for me to be formally excluded, my father could barely conceal his delight at this development and took the opportunity to celebrate by taking me for a boozy pub lunch on the way home.

For my part, I liked the way he enjoyed music, cried laughing at The Muppet Show, pottered about in the garden and kept the drinks cabinet well-stocked. He was also welcoming and interested in my friends, who were drawn to visit often, possibly by the well-stocked drinks cabinet.

But gradually we lost our way with each other: He became more intransigent, everything I liked was ‘rubbish’, he was needlessly cruel to our dog, he was wilfully racist, rotten to my mother and the cause of ugly arguments at the dinner table. (He actually put me off Sunday roasts. I couldn’t bear the tension and preferred to stay in my room. Can you imagine loathing anything so much that you’d give up roast dinners? This was serious.) When he came home less, often staying at his mother’s old house in London during the week, no one was disappointed.

Meanwhile, I went to university and he became convinced I’d been ‘got at’ by lefties. He would moodily rail against equality, tolerance or anything else I espoused, unmindful of his own descent into insular bigotry.

And he drank too much.

Gin had become his tipple. At work, at play, all day, every day. At the outset of his working life, when picking up a bottle of Guinness to share with my mother after work each day, he watched the smartly dressed man in front of him in the queue at the off-licence buy a bottle of gin. ‘I promised myself,’ he later told me, ‘that if I worked hard, one day that could be me.’ And now it was, except he was no longer sharing it with my mother. Or anyone.

A concerned doctor once asked my father how he felt if he went 24 hours without drinking. ‘No idea,’ he replied, with a shrug.

Looking back I think he was aware he was losing us, his family, that his influence was waning, and perhaps he was trying to shock his way back into being noticed. The drinking was solace, his escape. But the more he drank the more pissed off he got, and the nastier he became, to us and anyone else with the misfortune to be around him.

After university I lived in London and even though my father had by now also set up home there with his ‘lodger’, Mrs Wells, we saw little of each other. At this point he had fallen in line with my early teachers and considered me a wastrel. A lazy-arse. And he was right, I was. After an extended period on the dole in Camberwell I moved abroad to try being idle in another country for a bit.

It was while I was away that he became ill. Off the booze due to a violent episode of gastrointestinal bleeding, he suffered a terrifying incidence of the DTs in a taxi from the City to Suffolk (long story) during which he was attacked by giant spiders in polka-dot knickers. His solution to this was to get straight back on the booze in a very meaningful way, at which point his liver decided enough was enough and announced its imminent retirement by turning him bright yellow from top to bottom.

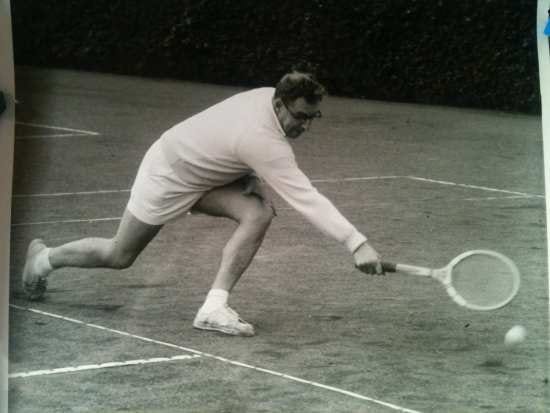

The prognosis wasn’t good. He was diabetic, his liver was cirrhotic and his kidneys were apoplectic. Plus he had a pile of associated cardiovascular diseases, one for every occasion. Worst of all, he reported, his tennis had gone to pot. I made peace with myself that the old bugger was on the way out.

His employer was good enough – having encouraged him to booze throughout his career (he even had a bar in his office) – to allow him to take early retirement, which he took to with gusto. I call this period The Rapprochement and count myself lucky to have shared it with him.

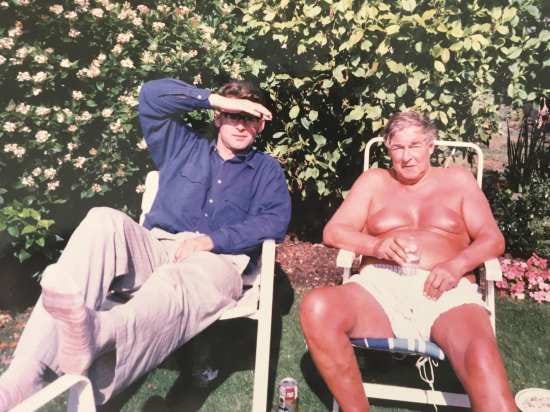

I have never witnessed an adult transformation like it. On day one of his retirement my father burnt his collars, joined two snooker clubs and took up smoking. He grew his hair, sat in the sun, ate fish and chips on the kerb, played piano, attended jazz gigs and went to the horse racing.

Mesmerised by this new man, I took to staying over at his place once a week. Not just for the largesse, of which there was plenty, but also for the company. We’d watch sport and films together, or play music; no longer was everything rubbish, now everything was a thrill. And he was eager to try new things: ‘Can you get me some of this hash everyone talks about?’

My friends came over, too, and enjoyed his generosity, and maybe more. I came down one morning to find a thank you note on the table, left to my father from two of my female mates who had slept over. It read, to my surprise, ‘Thanks for the fuck and booze!’ It was only later he admitted that he’d amended the word ‘tuck’ on the original missive. ‘It’s all about the legend,’ he’d said.

Having no work obligations myself, I joined him on extended road trips to Scotland and the North, to France or a seaside town near a racecourse. Wherever we went, he met and got chatting to people, this previously troubled character now radiant and easy-going, delighting folk with his stories and wheezy laughter.

On my 30th birthday I received a Happy Easter card from him, on which the word ‘Easter’ had been struck through and replaced with ‘Birthday’, in biro. It was a measure of how far our relationship had turned around that inside he had written ‘To my best mate’. I still have it somewhere.

Not long after this I recall him sidling up to me and saying that it wasn’t too late for me to take up a career in banking. I laughed, partly because obviously he still didn’t quite know me, but mostly because he’d proved to me, conversely (or inversely, or indeed perversely), that it’s never too late to jack in the rat race and rediscover yourself. He’d become what I am now – a happy Deserter.

He was, despite barbed asides about immigration, a different person: Expansive, kind, curious… Apart from in one regard. The booze.

To call my father’s attempts to stop drinking ‘cursory’ would be to do a disservice to the word. Non-existent would be closer to the truth. Indeed, in order to claim any success in this field my father was obliged to alter the definition of ‘drinking’ itself.

‘I’ve been very good today,’ he once told me, as I emerged from upstairs around lunchtime, ‘I’ve not had a single drink.’

‘Wow’, I said, genuinely impressed, until I happened to open the kitchen bin. ‘If you haven’t had a drink all day,’ I asked, ‘what are all these tins of beer doing in the bin?’

‘Oh, I’ve had beer,’ he replied.

He continued to be the only person I have ever known to receive Christmas and birthday cards from an off-licence.

Eventually, inevitably, the drink took its toll and his organs got together to coordinate a general strike. After a lengthy and debilitating stay in Kingston Hospital, he was gravely informed that he had taken his last drink and that Death was waiting for him at reception. That night, he snuck out for a final pint in a Norbiton pub, in his pyjamas. Three days later, he was dead.

I miss him, it would be odd not to, but I’m also aware of how he remains with me, of how his influence, good and bad, has shaped my life. Perhaps part of one’s life journey is observing and processing the behaviour of one’s parents, and working on eradicating their flaws from your own life. As no politician seems to be saying at the moment, those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it.

I do bloody love a pint, though.